![]() In an interview, the music duo Bracket opened up about their incredibly successful single Yori Yori. “We didn’t plan for it,” they said. They explained that they wanted a commercial song with unique characteristics.

In an interview, the music duo Bracket opened up about their incredibly successful single Yori Yori. “We didn’t plan for it,” they said. They explained that they wanted a commercial song with unique characteristics.

This is a common story as, over the years, there have been many Nigerian pop music successes without public knowledge of how they were put together. Not even the artists can reliably tell why the songs blew. Explainer essays examining these songs were often conjectures and intuitive.

In several instances, the successes of songs have been attributed to a noticeable factor: Instrumentation. When the beat slaps, there is the likelihood of huge success. In place of this, many have relegated the role of cultural insight in determining the success of singles in the Nigerian music industry.

Since 2008, no Nigerian song has blown without traceable insight backing it. Although the haphazard approach of Nigerian artists to music-making means arguing that they ruminate over things like audience preference is a largely unsustainable position. With repeated releases, this position becomes stronger. Artists tend to take a crude Dem go like this one approach, which is a good starting point — except that they do this only after writing and recording the music.

As a little exercise, cast your mind back to the beginning of the millennium. List some of the biggest hits, identify the insight backing each of the songs. W4‘s Control, Tony Tetuila‘s My Car, Eedris Abdulkareem‘s Mr Lecturer, Olu Maintain‘s Yahoozee, eLDee‘s Big Boy, and more recently Chinko Ekun‘s Able God (which is the main focus of this essay) all have immense cultural insight behind their lyrics. Identify those insights.

This article posits: If you stripped the original instrumentation of these songs, they would still strike a strong chord with the audience.

The Reception of “Able God”

Chinko Ekun dropped Able God in October 2018. The song featured Zlatan and Lil Kesh. It did not become a hit the instance it was released. But by November, it was rising exponentially on the streets and on charts.

According to Google Trends data, Chinko Ekun Able God was searched more times in the first days of its release. The song averaged 68 daily searches on Google, until it began to plummet in December.

Ironically, the song was raving offline, at events and concerts around the same time search rates were dropping on Google. In fact, disc jockeys used it as the ultimate crowd pleaser.

Dead bones would rise again whenever the song was cued in, its opening lines alone enough to do the magic.

What this suggests, in contrast with Google Trends data, is possibly a rise in peer-to-peer sharing. And a disadvantage of peer-to-peer sharing is the unreliability and unavailability of data.

Streaming data from many other platforms like Apple Music, BoomPlay and Deezer are not readily available. But on Spotify, Able God raked over 1 million streams. Considering Spotify is not available in Nigeria, this is a good outing. On YouTube Music, it did a meagre 15,000 streams while its video did 2.4 million views.

“See all these celebrity boys, they can’t afford what they bought.”

Chinko Ekun explained to Television Continental how Able God became a thing. The rapper had gone to a mall to buy some items. It was time to pay for the goods. He took out his card, and to the embarrassment of himself and his associates, the card was declined.

This thing, he continued, worried him so much he kept repeating to himself, “No more insufficient funds.” He would later cascade it into what would become one of the most recognizable call and response lines out of 2018.

No more insufficient funds,

a ti s’ise

No more insufficient funds,

a ti gb’ope.

“People around there in Shoprite were like, ‘See all these celebrity boys, they can’t afford what they bought’. Thank God for my manager that helped me that day. On our way home, while in the car, ‘No more insufficient funds’ kept on coming and we were like ‘No more insufficient funds,’” Chinko Ekun explained in the interview.

Able God is replete with the Nigerian story. The average Nigerian does not regard statistical and empirical guidelines. It shows in their interaction with technology.

At ATMs all over the country you will find people who know the total amount in their account but are still trying to withdraw above it. And this is not determined by the level of education of the individual. In fact, there are stories of university students who will, on their broke days, go to the ATM terminals just to try and see if something comes out. The man in front of the ATM who has been there for more than ten minutes might just be trying to withdraw an amount he does not have. A clear error code response is appearing on the screen of the machine, but he continues to press yes to another transaction. When he eventually leaves, he does so in the hope that on his next visit to the terminal, he will leave with actual notes in his pocket.

Also, pricing and money culture in Nigeria is linear. Nigerians do not see prices, especially electronic pricing, in double form. For example, if a product is priced at ₦1,200.47, that .47 does not exist. It is simply ₦1,200 here.

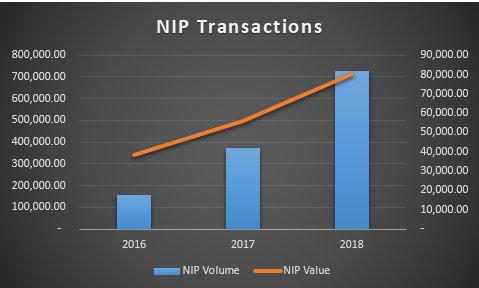

According to a recent Nigeria Interbank Settlement System (NIBSS) report, there was an increase in instant electronic payments in the country. Instant payments and online transactions have been rising consistently since 2016. That is to say, more Nigerians are now making electronic payments.

Over 700 billion NIP transactions happened last year alone. And in 2019, with the involvement of fintech companies targeted specifically at the unbanked, it is estimated that the rate of instant transactions will surpass 900 billion in volume.

![]()

NIBSS/ via @yinkanubi on Twitter

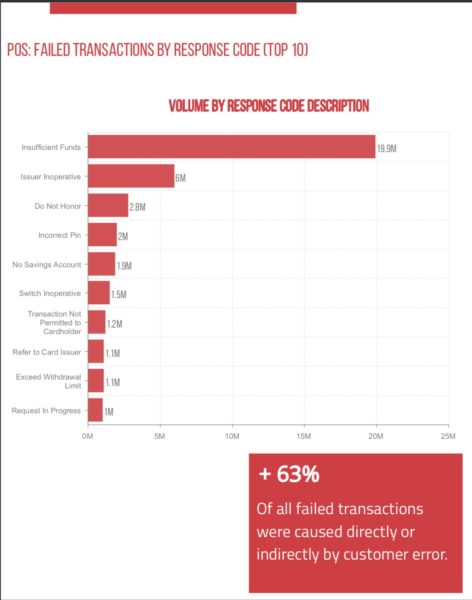

In more relevant statistics, on the top 10 response code for failed transactions on point of sale systems, “Insufficient funds” tops it with close to 20 million. Considering, this happened in 2018, Chinko Ekun’s transaction at the mall was one of those almost 20 million “insufficient funds” transactions. Little wonder why “no more insufficient funds” became so anthemic, even while the popularity of the song is rapidly declining.

![]()

NIBSS/via @DadaBen_ on Twitter

Perhaps what drove Chinko Ekun to make the song was a state of insecurity. How could he, a famous musician, be having insufficient funds? But by going into the studio to record the song, he managed to shrink this complex statistics into enjoyable music, even though the statistics was not out at the time. The success of Able God therefore goes beyond mere resonation; it is an amplification of a deeply rooted culture of hope and miracle.

Late in December 2018, during the height of the Detty December, Toke Makinwa wrote that she heard, in place of “Able God” as most folks did, “Ebuka” instead. Her tweet got so many reactions, with most claiming it was the media personality’s attempt to “shoot her shot” at the married Ebuka Obi-Uchendu.

During the same period, social media was rife with complaints that the song was a glorification of internet fraud, Yahoo Yahoo. There were indeed some problematic lines by Zlatan (one of the featured acts on the song), like the one quoted below on the song:

Omo Ase, o lo n toro oja kiri (kuro n’be)

T’o ye k’o lo ra lappy

Tete connect, k’iwo na le collect

K’o le rale si Lekki, k’o put e for rent

~ Zlatan Ibile on Able God

But there is more to the song than the glorification of fraud. Able God joins one of the many examples of how to make a Nigerian song people actually vibe to. And like Wyclef Jean said in his book: “A record that talked about what was going on at the time was something that everyone had to have back then because it was more than a record; it was a moment.” By making music that connects with the reality of the target audience, Chinko Ekun, Zlatan and Lil Kesh did not only make a song; they packaged an experience.

Nigerian music is getting to the point where musicians are now making music for a set of audience — a niche. A big example of this is the rapper, PayBac; with his The Biggest Tree album, he made music for sad people, people who have been in that place before. Boogey, with his Niveau Nouveau targeted at similar audience as PayBac. Timaya, Yemi Alade, who make music for lowest common denominator people while so-called upscalers hate. Omawumi, who makes live music and keeps promotional efforts targeted at folks who like live music.

“The success of Able God therefore goes beyond mere resonation; it is an amplification of a deeply rooted culture of hope and miracle.”

The problem with Nigerian artistes is: they want to eat the biggest slice, even when the biggest slice does not make up part of their audience. When this set of audiences boycott their music, they start to berate the industry for being harsh.

To address this issue, some musicians are now using data — numbers, as they are wont to call it. Numbers don’t lie. Yes, but numbers without cultural context is a lie. Artistes need to devote their time to listen to the little child nagging in their head. This is what most of these Nigerian artistes have learned to do: they mute the voice in their head and focus on satisfying their own vanity with the hope that the audience will lap it up. No. It is time for Nigerian artists to start engaging data scientists. Or become their own data scientists. After mining data, someone has to make sense of it. Another person has to do pre-testing to make sure they are on the right path. While this approach may not guarantee success, it increases the chances of success by a notch and that small notch might be what you/your artist may need to blow.

Chinko Ekun listened to that small voice. He did not let the need to sound smart overtake; and now, the people who should know him know him.

Gb’ese!

The post Notiki Bello: No More Insufficient Funds! Chinko Ekun’s ‘Able God’ Taps Into Our Reality appeared first on BellaNaija - Showcasing Africa to the world. Read today!.

It’s been two weeks since Nigerian youths began pouring out into the streets. Their one demand? That the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, infamously known as SARS, be scrapped. This squad, a unit of the Nigerian Police Force, was originally tasked with detaining and prosecuting those involved in crimes like armed robbery and kidnapping. Now, people are fed up and coming out to protest peacefully across the country because the unit has gone rogue. The goal is simple: scrap this unit and, in the long run, implement police reforms.

It’s been two weeks since Nigerian youths began pouring out into the streets. Their one demand? That the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, infamously known as SARS, be scrapped. This squad, a unit of the Nigerian Police Force, was originally tasked with detaining and prosecuting those involved in crimes like armed robbery and kidnapping. Now, people are fed up and coming out to protest peacefully across the country because the unit has gone rogue. The goal is simple: scrap this unit and, in the long run, implement police reforms. There have been talks about government officials cooking up schemes in order to make protesters discouraged, get tired and eventually give up on the

There have been talks about government officials cooking up schemes in order to make protesters discouraged, get tired and eventually give up on the